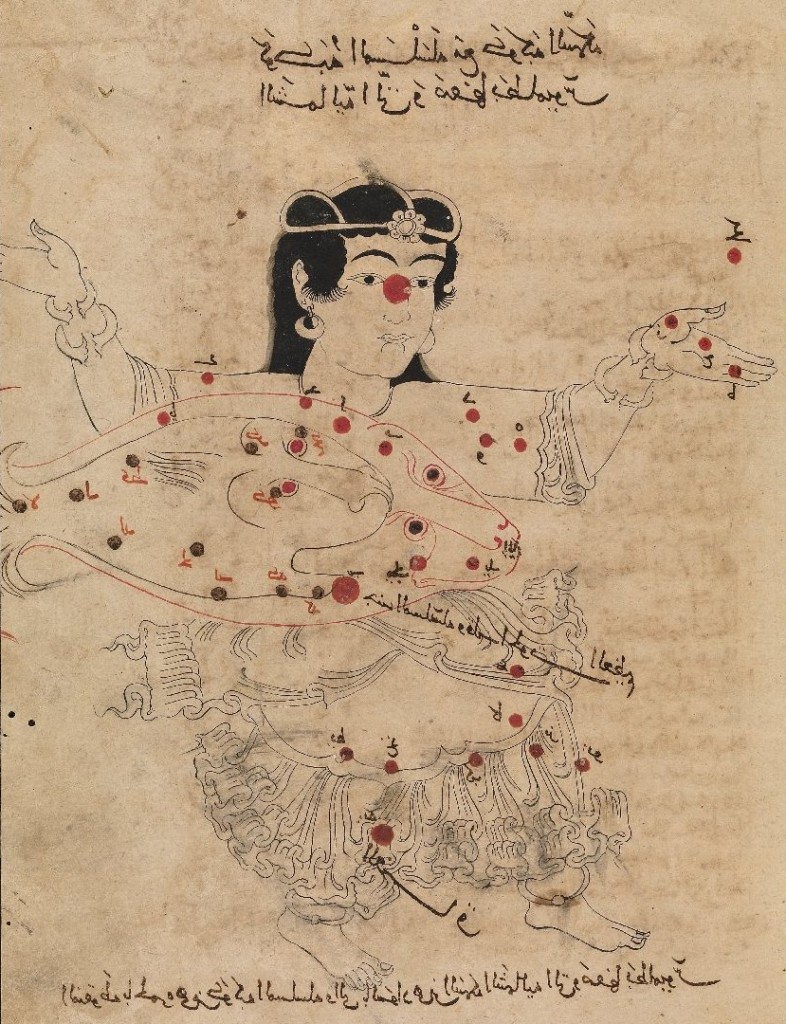

The constellation of Andromeda, from the earliest copy of the Al-Sufi manuscript, written c. 1009-1010 A.D. (Oxford, Bodleian Library MS. Marsh 144, page 167). The image is reversed here. This is how the constellation would appear to an observer.

The Andromeda Galaxy holds several distinctions. It is the closest galaxy to our own (the Milky Way) – about 2.4×1019 km from the Earth. It is also the largest and most massive galaxy in the Local Group, which includes about 45 galaxies.

Its size and proximity make it visible to the naked eye.

When Claudius Ptolemy of Alexandria made a catalogue of all known astronomical objects in the second century A.D., his only instrument was the naked eye. His Almagest lists five stars as ‘nebulous’, together with a ‘nebulous complex’. These data were the gold standard in astronomy right through the Middle Ages.

But Ptolemy did not include the Andromeda Nebula. This nebula, which is in fact the Andromeda galaxy, was first described by the Persian astronomer Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi (903-986 A.D.). Al-Sufi worked at the Buyid court in Isfahan. Some time around 964 A.D., he wrote the Book of Pictures of the (Fixed) Stars, which was a synthesis of Graeco-Roman knowledge contained in the Almagest with Arabic astronomical tradition.

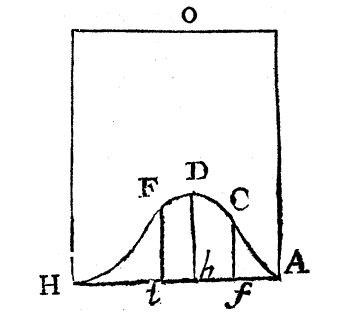

The manuscript consisted of text and accompanying diagrams. The drawing of the constellation of Andromeda as described by Ptolemy, or “the woman in chains” in Arabic, is superimposed by the Big Fish, an Arabic constellation not found in the Almagest.

The text describes a “little cloud” (latkha sahabiya) lying near the mouth of the Big Fish. The drawing shows it as a small clump of dots.

This little clump is the Andromeda Galaxy. That drawing is the first image of another galaxy.

Al-Sufi’s text made its way into the Latin West some time during the 12th century, and was translated into Latin as the Liber locis stellarum fixarum. It has been attributed, with varying degrees of certainty, to an unknown scribe working at the court of William II of Sicily (1155-1189). The earliest copy of this manuscript in held in the Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal in Paris (MS. 1036) and dates from around 1250-1275. It was probably made in Bologna, in northern Italy.

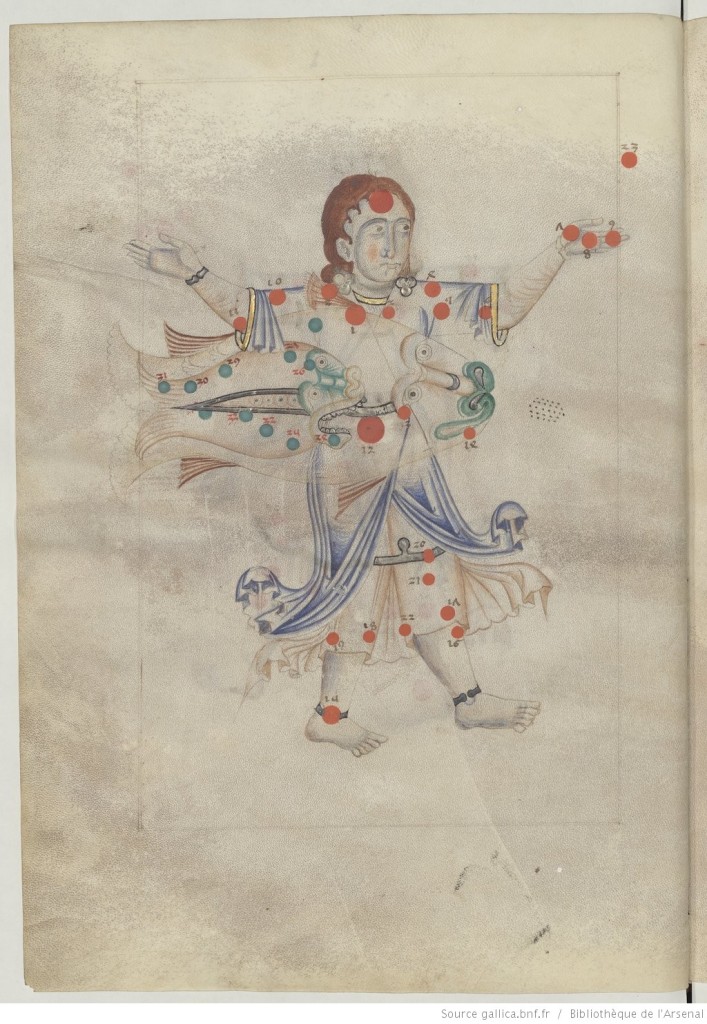

Drawing of Andromeda, from the Liber locis stellarum fixarum, Paris, Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, MS. 1036, fol. 17v. Just like the Arabic Al-Sufi manuscript, it shows the Andromeda Galaxy as a little clump of dots.

The same constellation, from yet another Latin copy of the Al-Sufi manuscript (so-called Sufi Latinus text). The dots marking the nebulous spot can be seen to the right of the Big Fish’s mouth. This manuscript was made in 1428 in northern Italy (Gotha, Forschungsbibliothek, MS. Memb. II 141).

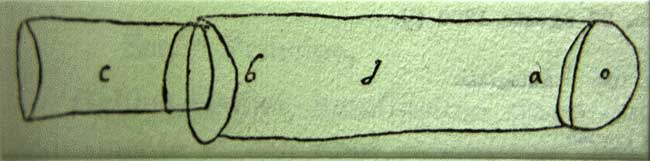

The earliest known photograph clearly showing the Andromeda galaxy was taken by Isaac Roberts using a twin telescope (20-inch reflector & 7-inch refractor) by Howard Grubb of Dublin. It was taken with an exposure of 4 hours on 29th December 1888 at his observatory & home at Maghull, near Liverpool. It is the first photograph to show the spiral structure of Andromeda, and the first to show the structure of any galaxy.