I have recently found myself talking past my audience on the subject of Einstein’s famous equation \(E=mc^2\). They were convinced that there’s more inside that than Einstein ever explained, and either he knew there was more or he didn’t. I’m quite sure Einstein knew his subject, I have been at some pains to explain how the famous equation is a result of the postulates of Special Relativity, and there is nothing mystical about the \(c^2\). So here is the derivation.

2. Postulates of Special RelativityPostulates in physics are like axioms in maths. They are the principles on which the theory is built.

Special Relativity is built on the following two postulates:

- Principle of Relativity: The laws of physics are identical in all inertial reference frames.

- Constancy of the Speed of Light: The speed of light in vacuum has the same value \(c\) in all inertial frames, independent of the motion of the source or the observer.

These two postulates imply that spacetime transformations between inertial frames are given by the Lorentz transformations and that space and time are not independent entities.

2.1. What are the Lorentz transformations?Before we go any further, we need to explain Lorentz invariance and Relativistic kinematics.

Consider two inertial frames \(S\) and \(S’\), with \(S’\) moving at constant velocity \(v\) along the \(x\)-axis of \(S\). The Lorentz transformations are \[ x’ = \gamma (x – vt), \qquad t’ = \gamma \left(t – \frac{vx}{c^2}\right), \] where \[ \gamma = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1 – v^2/c^2}}. \]

The invariant spacetime interval \[ s^2 = c^2 t^2 – x^2 – y^2 – z^2 \] is preserved under these transformations. This invariance underlies the structure of relativistic dynamics.

3. Relativistic momentumIn order for momentum conservation to hold in all inertial frames, the Newtonian definition of momentum must be modified. The correct relativistic expression is \[ \mathbf{p} = \gamma m \mathbf{v}, \] where \(m\) is the invariant (rest) mass of the particle. The rest mass is often denoted \(m_0\).

This form is uniquely determined (up to a multiplicative constant fixed by the Newtonian limit) by the requirement that momentum be conserved in all inertial frames.

This is an important point, and possibly the only point where the notion of agreement with experiment comes in. So here it is.

3.1. On the uniqueness of Relativistic momentum and the Newtonian limitIn Special Relativity, the momentum of a particle is given by \[ \mathbf{p} = \gamma m \mathbf{v}, \] where \(\gamma = 1/\sqrt{1 – v^2/c^2}\) and \(m\) is the rest mass.

From a purely mathematical standpoint, one could write a more general form \[ \mathbf{p} = k \, \gamma m \mathbf{v}, \] where \(k\) is a multiplicative constant independent of velocity. This freedom arises because the requirement of Lorentz invariance and momentum conservation alone does not fix the overall scale of momentum.

The value of \(k\) is uniquely determined by the Newtonian correspondence principle, which demands that in the low-velocity limit (\(v \ll c\)) relativistic momentum reduce to the classical form: \[ \mathbf{p} \approx m \mathbf{v}. \] Imposing this condition immediately fixes \(k = 1\), ensuring agreement with well-tested classical mechanics at ordinary speeds.

It is therefore the combination of Lorentz symmetry and the Newtonian limit that uniquely determines the standard form of relativistic momentum.

Could dropping the Newtonian limit lead to new physics?

Mathematically, one could imagine abandoning the Newtonian limit, allowing \(k \neq 1\). In such a hypothetical framework, \[ \mathbf{p} = k \, \gamma m \mathbf{v}, \qquad E = k \, \gamma m c^2, \] still satisfies relativistic invariance, but it would lead to predictions inconsistent with experiments at low velocities. But we’re doing physics, not maths. We observe and measure and test. Now Classical Mechanics is extremely well-tested, so any deviation in the low-speed regime is experimentally ruled out.

True new physics beyond Special Relativity would therefore require modifications to one or more fundamental assumptions, such as:

- Violation of Lorentz invariance at high energies or small scales. (This violates Special Relativity)

- Breakdown of energy–momentum conservation. (This violates all physical theories)

- Non-Minkowski structure of spacetime. (Which it is in General Relativity. But Einstein knew this. In fact he formulated General Relativity himself.)

In such regimes, the standard relation \(\mathbf{p} = \gamma m \mathbf{v}\) could be altered in a physically meaningful way, potentially giving rise to observable deviations from classical and relativistic predictions. In fact the meaning of \(E\) becomes more subtle in General Relativity.

Of course Special Relativity holds locally (i.e. in a small enough region of spacetime) in General Relativity, so all of the equations of Special Relativity are still valid locally. Again, Einstein himself knew this.

3.2. Work–energy relationBack to our derivation. Now comes a bit of physics which will be familiar to anyone who studied it in secondary school.

The work done by a force is equal to the change in energy: \[ dE = \mathbf{F} \cdot d\mathbf{x}. \] Using \(\mathbf{F} = d\mathbf{p}/dt\) and \(d\mathbf{x} = \mathbf{v}\,dt\), we obtain \[ dE = \mathbf{v} \cdot d\mathbf{p}. \]

Substituting the relativistic momentum, \[ dE = \mathbf{v} \cdot d(\gamma m \mathbf{v}). \]

Using the identity \[ d\gamma = \gamma^3 \frac{\mathbf{v} \cdot d\mathbf{v}}{c^2}, \] one finds after straightforward algebra \[ dE = mc^2\, d\gamma. \]

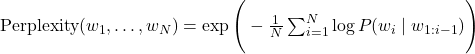

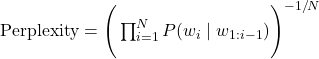

3.3. Total Relativistic energyIntegrating from rest (\(v = 0\), \(\gamma = 1\)) to velocity \(v\), \[ E – E_0 = mc^2 (\gamma – 1). \]

Thus the total energy of a particle is \[ E = \gamma mc^2, \] where \(E_0\) is the energy when the particle is at rest.

3.4. Rest energy and mass–energy equivalenceFor a particle at rest, \(v = 0\) and hence \(\gamma = 1\). The energy reduces to \[ E_0 = mc^2. \]

This result shows that mass itself is a form of energy. The quantity \(mc^2\) is the intrinsic energy associated with a body even in the absence of motion.

3.5. Energy–momentum RelationEnergy and momentum combine into a four-vector \[ P^\mu = \left(\frac{E}{c}, \mathbf{p}\right), \] whose Lorentz-invariant norm (or the `length’ of a vector in 4-dimensional Minkowski spacetime) is \[ P^\mu P_\mu = \frac{E^2}{c^2} – \mathbf{p}^2 = m^2 c^2. \]

Rearranging gives the general relation \[ E^2 = p^2 c^2 + m^2 c^4, \] which reduces to \(E = mc^2\) for a particle at rest.

3.6. That’s itThere it is.

The equivalence of mass and energy is not an independent assumption, but a direct consequence of:

- the Lorentz symmetry of spacetime implied by the postulates of Special Relativity, and

- the requirement that energy and momentum be conserved in all inertial frames.

Thus, \[ \boxed{E = mc^2} \] emerges from the principles of Special Relativity.